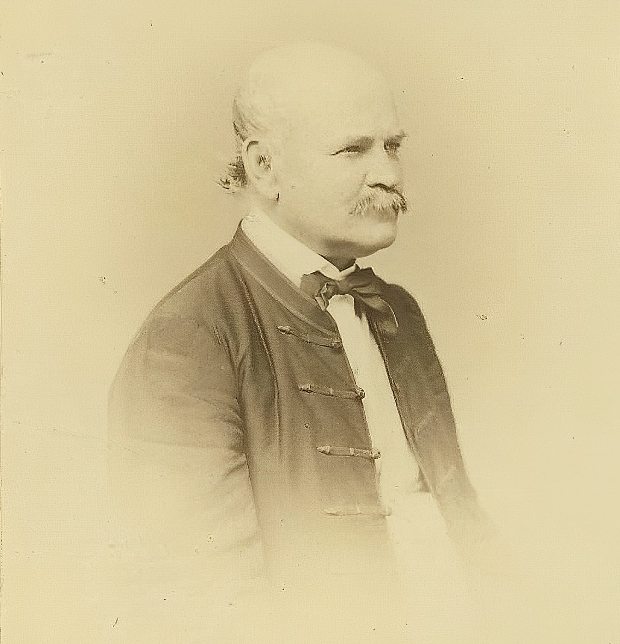

The Subject—Ignaz Semmelweis

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865), a Hungarian physician, is remembered as one of the earliest and clearest examples of proper empirical reasoning in medicine. His career illustrates both the hardships faced by innovators in science and the enduring importance of verification through data over the allure of elegant but unfounded theories.

Hardships and Rejection

Semmelweis worked at the Vienna General Hospital in the mid-19th century, where puerperal fever (childbed fever) was a leading cause of death among mothers. Despite his careful investigations, his colleagues largely dismissed his findings. He endured ridicule, professional isolation, and eventual dismissal from his position. Later in life, he faced declining mental health and died in obscurity, his work recognized only posthumously. He also suffered mental distress because he could not comprehend how others failed to see what he demonstrated so clearly. The refusal of his peers became his lifelong obsession, and he came to speak of little else.

Method and Discovery

Semmelweis approached the problem by comparing two maternity wards within the hospital: one staffed by doctors and medical students, the other by midwives. He noted that mortality rates in the doctors’ ward were significantly higher. Rather than attributing this to vague “miasmas” or to social factors, he systematically investigated potential causes. His breakthrough came when he identified that doctors were often moving directly from autopsies to childbirth without disinfecting their hands.

Empirical Evidence

To test his hypothesis, Semmelweis instituted the practice of washing hands with a chlorinated lime solution before patient contact. The results were striking: mortality rates in the doctors’ ward dropped from over 10% to below 2%, matching the rates in the midwives’ ward. This reduction provided a clear, reproducible demonstration of the effectiveness of handwashing. His approach exemplified a model of scientific reasoning grounded in observation, hypothesis, and verification.

Epistemological Lesson

Semmelweis’s case shows that good epistemology lies in empiricism and verification rather than in the elegance of explanation. Many physicians of his time rejected his findings because they conflicted with prevailing theories about disease causation, which seemed neater or more probable within the medical worldview of the day. Yet the data spoke plainly: handwashing saved lives. The lesson is enduring—sound science rests not on what is most beautiful or theoretically satisfying, but on what is tested, observed, and confirmed. Empiricism, however unsettling, rules supreme.